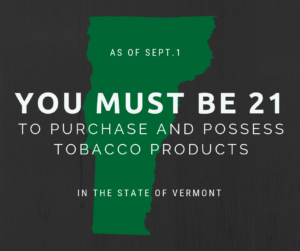

Vermonters must be 21 to purchase and possess tobacco products starting Sept. 1

Law aims to protect youth from harms of e-cigarettes and reduce smoking rates

BURLINGTON, Vt – Starting September 1, [2019] Vermonters must be at least 21 years old to purchase and possess tobacco products or paraphernalia. The new law also includes tobacco-substitute products, such as e-cigarettes. Health officials say the increase in buying age will help protect youth from nicotine addiction and potentially toxic chemicals.

Commonly known as Tobacco 21, the new law is expected to reduce smoking rates over time and ultimately save lives. An estimated 95% of adults start smoking by age 21, so restricting access to these products will help prevent young Vermonters from ever taking it up.

“We’ve made great strides against tobacco use, but the popularity of e-cigarettes and vaping continues to skyrocket among our youth,” said Health Commissioner Mark Levine, MD. “We are also seeing evidence of increasing rates of health problems associated with vaping.”

According the Vermont Youth Risk Behavior Survey (YRBS) there was a significant increase in the percent of students who have ever tried e-cigarettes, from 30% in 2015 to 34% in 2017. Among high school students in Vermont, 12% said they used electronic vapor products in the past 30 days.

What’s in a “pod”?

A single 5% “pod” of liquid nicotine used in e-cigarettes can contain as much nicotine as an entire pack of cigarettes. Teens and young adults are uniquely vulnerable to the effects of nicotine, and more likely to get addicted. Exposure to nicotine in adolescence can impact attention, learning, mood and impulse control. The aerosol that users breathe from e-cigarettes can contain nicotine and other toxic chemicals, including formaldehyde and arsenic.

Dr. Levine said that while e-cigarettes are less harmful to adults than combustible cigarettes, they are never safe for teens and young adults, making this new law all the more necessary. “These cyber-cigarettes, with their thousands of flavors, represent a 21st Century version of big tobacco’s decades-long push to market and promote their products to youth,” said Dr. Levine. “Society always races to keep up with technology. This law helps to close the gap in favor of protecting public health.”

With the enactment of Act 27, Vermont joins 17 states, the District of Columbia, Guam and more than 480 municipalities with a Tobacco 21 law.

Two related laws went into effect in July that prohibit the online sales of e-cigarettes and liquid nicotine, and subjects e-cigarettes and liquid nicotine to the same 92% tax already assessed on tobacco-related products. These laws, in combination with Tobacco 21, help strengthen statewide tobacco prevention efforts to discourage teens and young adults from using these products.

Want to Learn More?

Health officials urge anyone looking for help to quit smoking or the use of any kind of tobacco product to visit 802quits.org.

Read the Vermont Tobacco Prevention Laws fact sheet and find more information about tobacco, e-cigarettes, at healthvermont.gov/wellness/tobacco.

Schools can also find resources specific to their communities by using our new Electronic Vapor Product Education Toolkit.

Press Release from the Vermont Department of Health, August 29, 2019