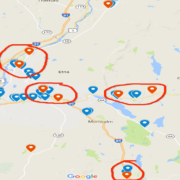

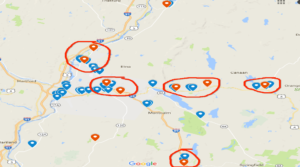

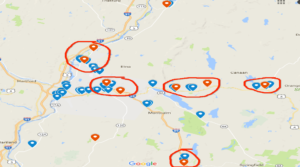

A map of the area where the environmental scan occurred. Blue pins denote retail stores. Red pins denote schools.

Observations from a Community Tobacco and Alcohol Environmental Scan: Advertisement and Sale Practices in the Upper Valley of New Hampshire

This article was written by Bryan L’Heureux, MPH Candidate, University of New England, describing the study he conducted on behalf of ALL Together in the Fall of 2017. Full Environmental Scan Report.

Background and Methods

There exists an interconnectedness between our environment and our health. In many cases, things that we are exposed to every day, such as the air we breathe or the water we drink, can directly affect our health. However, our environment can also influence decisions we make and the behaviors we participate in, which can then indirectly effect our health. This type of environmental influence sometimes occurs through the sale and advertisement practices we are exposed to within our communities and surroundings. With stricter restrictions on the ways tobacco companies are allowed to advertise via radio and television, it is not surprising that over 92% of tobacco advertising occurs at the point-of-sale within the retail environment1. That being said, one of the most vulnerable populations to advertisements are our youth and adolescents, who, conveniently, are also potential new customers in the eyes of tobacco manufacturers2. Keeping that in mind, when looking at retail density as it relates to the location of schools within the population of interest, the Upper Valley of New Hampshire, it is curious to note that there are clusters of retailers selling and advertising tobacco and alcohol in these areas. For this reason, in an effort to decrease tobacco initiation and alcohol misuse, it very important to be aware of practices used within our community that can influence behaviors related to negative health outcomes, such as tobacco initiation and alcohol misuse.

Conducting an Environmental Scan

In an effort to become more aware of the sale and advertisement practices used to sell tobacco and alcohol in the Upper Valley region of New Hampshire, I conducted an environmental scan of retailers in the community with the support of Upper Valley ALL Together and Dartmouth-Hitchcock. ALL Together, which is the Substance Misuse workgroup of the Public Health Council of the Upper Valley, is a community resource for prevention, intervention, treatment, recovery, and advocacy around substance misuse and suicide prevention. The goal of this scan was to identify practices that have the potential to influence initiation of tobacco use and/or alcohol misuse in an effort to make a collective change toward heathier advertisement and sale methods in our community’s retail environment.

The environmental scan itself consisted of a survey meant to identify risk factors as well as protective factors for tobacco and alcohol initiation as they pertain to advertisements at the retail level. For the purposes of this scan, only retailers on the New Hampshire side of the Upper Valley were observed. This scan consisted of nine towns; Lebanon, West Lebanon, Hanover, Canaan, Enfield, Grantham, Orford, Piermont, and Plainfield. I spent approximately 5-10 minutes in each retailer, simply making observations pertaining to location and types of products/advertisements in

each store. For example, in each store I tried to observe if there was tobacco on counters, near candy, toys or energy drinks, if there is alcohol in the same cooler as non-alcoholic beverages, if there are advertisements with cartoons or celebrities, if there are themed displays, or if alcohol is displayed with items that would promote binge drinking. In all, forty-five stores were observed, providing meaningful data about the environment of tobacco and alcohol advertisements/sales in the Upper Valley.

Snapshot of the Region: Alcohol

Through the observations made during the survey, it is clear there are a number of things our community is doing right in terms of selling and advertising alcohol. For example, out of the stores that sold alcohol (n=41, 91%), 59% of those stores kept alcoholic beverages either in a different cooler or out of eyesight from the non-alcoholic beverages. With only 41% of the stores keeping alcohol in the same cooler as non-alcoholic beverages, it is clear that while there is some room for improvement, our community is doing relatively well in this area. Furthermore, in terms of

An alcoholic beverages case with ping pong balls hanging on the door.

advertising these products, only 7.3% of the stores sold items that promote drinking games/binge drinking (such as red solo cups and ping pong balls) with alcoholic beverages. A number of stores did however have displays for alcoholic beverages that could be confused as non-alcoholic or utilized themed displays in their advertisement practices (31.7% and 19.5%, respectively). Working with these retailers to make small changes in these areas would be small changes that may have a large impact on the way youth perceive alcohol and the culture around drinking in general.

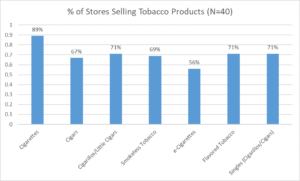

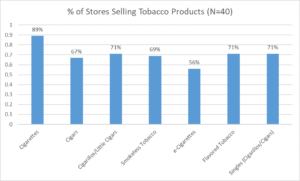

Snapshot of the Region: Tobacco

In the Upper Valley, of the stores surveyed, 90% (n=40) sell tobacco. The chart below delves into the various types of tobacco that are sold in the region, however, it does not distinguish between the various types of smokeless tobacco, such as snuff, snus, chew etc. due to the similar appearance in the products making it difficult to differentiate between the products when completing the scan.

A number of things are important to point out in terms of the placement of tobacco products in the retail environment as well. For the most part, tobacco products were kept out of reach from the customer, behind the point-of-sale (48%). However, there were also a number of instances where tobacco products and/or advertisements were placed near candy, toys, or energy drinks (17%), or were placed on counters, within reach of the customer (35%). This is an area that can easily be targeted for improvement; store owners can easily and cost effectively change the placement of these products to promote a healthier environment and help mitigate normalcy of these tobacco products for our youth.

Finally, a number of different, common, advertising practices for tobacco products can be observed in the Upper Valley. Cross promotions (a discount/promotional effort meant to get individuals to try different types of tobacco) were seen in 10% of the stores. More commonly were price promotions in general (77%); these advertisements offer a “special price” or utilize mobile coupons. Placement of tobacco advertisements is also an area of concern; as was mentioned above, ensuring that advertisements are not placed in the faces of our youth is important in prevention efforts. 27.5% of the stores in our community place advertisements at or below three feet, showing that while many stores are following good practice, there is still room for improvement. Furthermore, 35% of the stores that sold tobacco had advertisements for these products, including cigarettes, smokeless tobacco, and e-cigarettes, from the road.

Advocating for a Healthier Retail Environment

After collecting this information, I sent a letter specific to each store celebrating what they were doing well, as well as giving them some tips and tricks for ways that they could change the environment of their store to promote a healthier community. This letter called for collective action and change, rather than placing the burden on any one retailer or individual. The hope was that framing the letter in this way would allow the retailers to feel empowered to have a positive effect on the health of the community that they live and do business in.

As a community, we can advocate for limiting retail tobacco/alcohol advertisements, both inside retail stores and at the point-of-sale, as well as advertisements that are visible from the road. Furthermore, we can work with retailers to promote practices, such as keeping these products away from items that are geared toward children and adolescents, such as candy and energy drinks.

Making these small changes can have a large impact on the overall environment of our community and the perceived culture around these products, showing that as a whole, we value healthy decisions and want to do what we can to help young people make the decision not to use tobacco or misuse alcohol.

References:

- https://www.ftc.gov/system/files/documents/reports/federal-trade-commission-cigarette-report-2012/150327-2012cigaretterpt.pdf

- https://www.surgeongeneral.gov/library/reports/preventing-youth-tobacco-use/index.html

The statistics about falls involving senior citizens are troubling: According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 1 in 4 adults 65 and older fall each year, and the numbers are rising.

The statistics about falls involving senior citizens are troubling: According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 1 in 4 adults 65 and older fall each year, and the numbers are rising.